Menstrual Oppression in India

an exploration of menstrual taboos, untouchability and glimpses into the female healthcare crisis

Chapter 1: Introduction

Women have long been the bearers of generational curses—burdens born from patriarchal impositions which evolve into pillars of honour by which a woman’s virtue is decided. These curses have become so ingrained in our very speech and thought, making shame and silence almost characteristic of a ‘good woman’. One of the clearest manifestations of this is menstrual oppression, a prime example of how a natural process has been transformed into a source of stigma and control.

When I bled for the first time, I was in the middle of a science exam. A bright red splotch of blood stained my white school skirt. I remember struggling to adjust the straps of my school bag so it hung closer to the back of my knees, covering the stain. Somehow, I knew it was something I had to hide.

At home, my mother and grandmother huddled closer trying to decide what must be done next. A phone call to my father, to my relatives, plans for rituals with turmeric and kumkum and head washes I can’t remember too much of now. My mother unfolding the sanitary napkin, teaching me to use it. Within a few minutes, something shifted around and within me. Even if my parents didn’t extend any prejudices, to the people around me, I was more woman less daughter from then on.

Just then, my younger brother who was around 8 years old, came running into the room and hugged me. A shrill voice erupted, cutting through the thick air in the room—a sound I had never heard before. It was my grandmother. The same grandmother who had always been calm and angelic, who had never raised her voice, not even in the harshest moments. It was jarring to see someone like her react with such vitriol. She pushed my brother away and said something along the lines of: Akka is dirty, don’t touch her.

The Tamizh word for dirt is அழுக்கு; azhukku, a word so harsh with its arrangement of syllables. In that moment, my mother looked my grandmother in the eye and said: Amma, we’re not doing that in this house. A sentence so simple, a manifestation of the result of years of her isolation, untouchability and shame. Generational curse, broken.

Chapter 2: Menstrual Myths and Practices

I'll admit it, I write this section with so much fear in me. As a young woman with a strong sense of faith that extends beyond religion, I know to respect ancient traditions in all cultures. At the same time, I’m constantly trying to understand the origins of such practices and how much of it I must take for myself.

Consider Sati, a practice in which a widowed woman was asked to burn herself on the funeral pyre of her husband. People might justify this practice by saying that our ancestors were considerate about the plight of a widowed woman and suggested such a thing to prevent her from the sufferings she would have to undergo if she lived on. Do I even need to establish an argument against such a logic? I feel similarly about the myths that surround menstruation.

We believe most attitudes surrounding women in our ancient texts establish their importance and respect. Throughout India, several festivals are celebrated to commemorate the menstruation of the rivers, the earth and so on. The Ambubachi festival is perhaps the most famous one, celebrated in Assam is one of the largest gatherings in Eastern India, commemorating the menstruation of Goddess Kamakhya. The main temple is closed for 3-4 days and no one is allowed to enter it. During this period, even Mother Earth is considered to be menstruating. Some also believe that the Brahmaputra river turns red (either due to cinnabar or because of priests throwing in vermillion into the waters).

However, there are texts that have harmful, demonising perspectives of women. It's easy to say that we must adopt a 'take what's good and leave out the rest' attitude but that's not possible when the result of such harmful ideas bleed into our practices, speech and very thought in the present.

Take for example these verses from the English Translation of the Garuda Purana:

2.32.9 "A woman in her menses is an outcaste on the first day, a slayer of brahmana on the second day and a washerwoman on the third. She becomes pure on the fourth day.

2.32.10 "After seven days, she becomes pure enough to take part in the worship of manes and deities. If conception takes place within seven days the progeny is impure.

2.32.15-16 "Conception usually takes place within eight days. On the fifth day the woman is given sweet dishes which is a good tonic for the embryo. Astringent and pungent things should not be taken at all. The woman's parts can be likened to a medicinal vessel. The seed of a man can is like an ambrosial food.

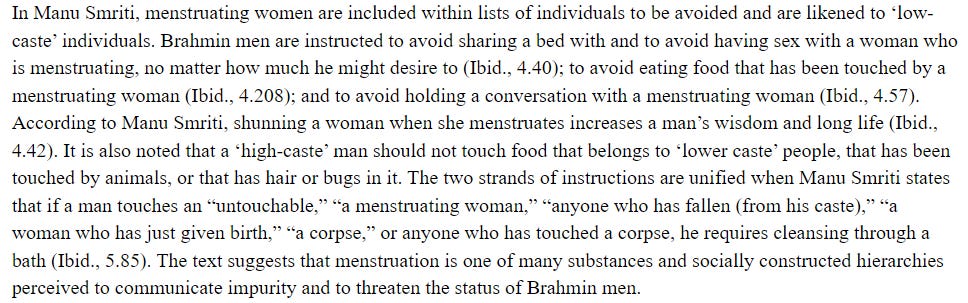

In Chapter 11 of The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, the author states:

In their review of Menstrual symbolism in India, Dr. Aaryaa Ashutosh Joshi connects menstruation with the earth and rivers. The author explores how people believe the rivers and earth too go through the stages of menstruation, pregnancy and childbirth. Several festivals are observed during the ‘pregnancy’ of rivers, the flourishing of the earth and to celebrate the first period of a young girl. I was also intrigued by the Garuda Purana’s take on rivers and womanhood:

1.109.39. The river undermines the banks and the woman causes the fall of the family. The course of rivers and women is wayward and cannot be checked.

In this section, we’ll consider some menstrual taboos and their justifications after which I will provide my thoughts at the very end. They all seem to be saying the same thing, just in different ways—these laws were laid down by our ancestors in an attempt to protect and support women during menstruation. We’ll consider its truth and point towards the central fallacy in such statements.

As we embark on the task of understanding common menstrual taboos, we must also remember that menstrual taboos and traditions vary widely, not only between different states and communities but also among various intersections of caste, class, and religion. I acknowledge that the scope of this analysis is limited and does not encompass the full range of cultural, religious, and regional practices across India.

A woman musn’t enter a temple/religious places

In 2018, the Supreme Court of India declared that all women would be allowed to enter the Sabarimala temple, causing nation-wide debates and uproar. A common belief is that the deity is a brahmachari, a celibate and chose his abode on the mountain top to abstain and isolate himself. Several temples in India prohibit the entry of men too and such prohibitions are believed to arise from the honouring of traditional practices, not with the aim of discrimination.

What about temples where women are not allowed only during their period? To this, several people argue that temples are marvels of architecture which are constructed with attention to magnetic fields, chakras and other such spiritual sciences. All of these are believed to be harmful to menstruating women. In a lot of places, women are forbidden to perform poojas regardless of menstruation and to that I’d just like to remember what Swami Vivekananda once said:

In what scriptures do you find statements that women are not competent for knowledge and devotion? In the period of degradation, when the priests made other castes incompetent for the study of the Vedas, they deprived the women also of all their rights. Otherwise you will find that in the Vedic or Upanishad age Maitreyi, Gargi, and other ladies of revered memory have taken the places of Rishis through their skill in discussing about Brahman. In an assembly of a thousand Brahmanas who were all erudite in the Vedas, Gargi boldly challenged Yajnavalkya in a discussion about Brahman. Since such ideal women were entitled to spiritual knowledge, why shall not the women have the same privilege now? What has happened once can certainly happen again. History repeats itself. All nations have attained greatness by paying proper respect to women. That country and that nation which do not respect women have never become great, nor will ever be in future. The principal reason why your race has so much degenerated is that you have no respect for these living images of Shakti.

from The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda/Volume 7/Conversations And Dialogues/XVIII

A woman mustn’t enter the kitchen

In olden days, people usually lived in joint families, meaning that a woman would have to cook for at least more than 10 people at multiple times of the day. Though there would be a division of labour between the women of the house, the domestic load is still heavily placed on individual women because of the increased number of family members. People believe that this rule was laid down to relieve women of domestic duties and allow them few days of rest, which is vital during menstruation.

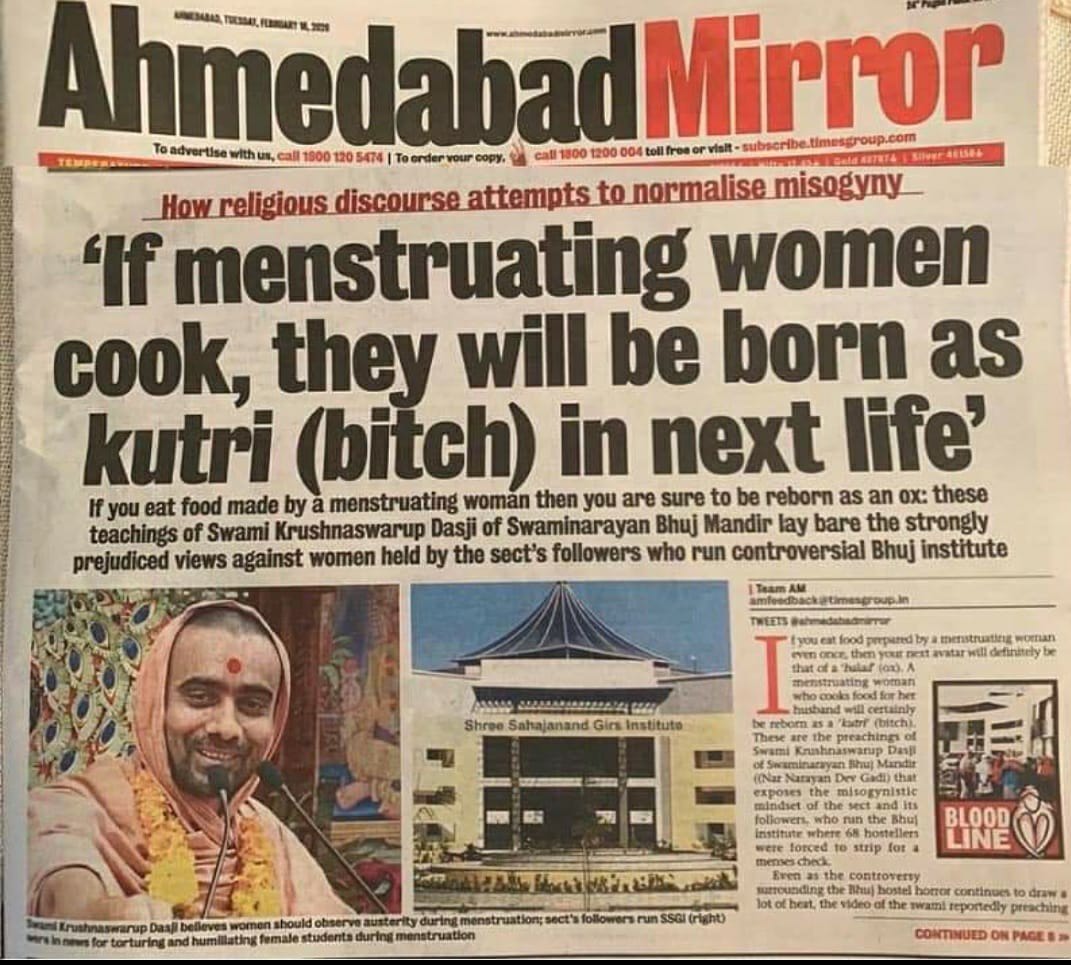

A few years back, a video of a Krushnaswarup ‘Swami’ went viral all over the internet for his regressive statements. He claimed that menstruating women who cook food will be born as dogs in their next birth while husbands who eat that food will be reborn as oxes. It so happens that the temple he is associated with was under public scrutiny for its practice of checking female undergarments to verify if they were menstruating or not.

A woman must have no physical contact with other members of the family or their things

If she does, the other person is often asked to take a ritualistic bath to cleanse themselves off her impurities. Once again, people believe that such a rule was laid out so that women wouldn’t have to be burdened by domestic duties.

A woman must stay in a separation hut, sleep on a separate mat and eat from a separate plate. She is also not allowed into the house

In many places, usually remote villages, menstruating women are often cast off to stay in frugal huts during their menstruation period. In some towns, women will often be asked to stay in the backyard or in a separate room where they must eat from a separate plate and sleep on a secluded mat on the floor. Once again, the justification for this practice is to give the woman her own privacy during the days of bleeding, especially considering the fact that in olden days, there weren’t very efficient methods of managing the flow of period blood.

Now that we’ve taken a look at some of the common menstrual taboos practised in India, some even to this day, I’ll leave my thoughts on these practices here.

In her essay (which I highly encourage you to read for a perspective from a voice that is often unheard in such conversations), Personal Narrative: Caste Is My Period, Deepthi Sukumar talks about the hypocrisy in seeking an abolishment of period untouchability without considering the same practice that is performed against dalits and members of other such marginalised groups.

When it comes to the practice of observing untouchability against menstruating women, I find that the common reasons people give for the isolation is to protect, to relieve, to empower. People are quick to justify this practice by stating one of these reasons and trying to establish the idea that these rules were laid out in thoughtfulness. For my own sanity, I’ll believe in this. How then, do we justify the systemic shame, the humiliation and ignominy women have been subjected to for centuries?

We forget that these reasons are valid only if the practice began and ended with repose. The core of the practice of isolating menstruating women lies in treating them as untouchables, calling them ‘theetu’ and paving way for a culture where the woman learns to be ashamed of herself and her body. Yet again, women and their bodies are used as tools under the name of religion.

Chapter 3: The Hazards of Menstrual Sanitation

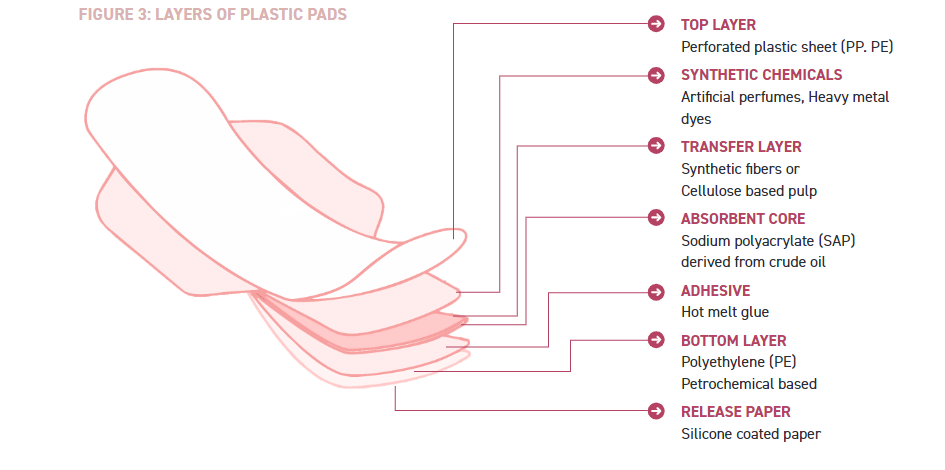

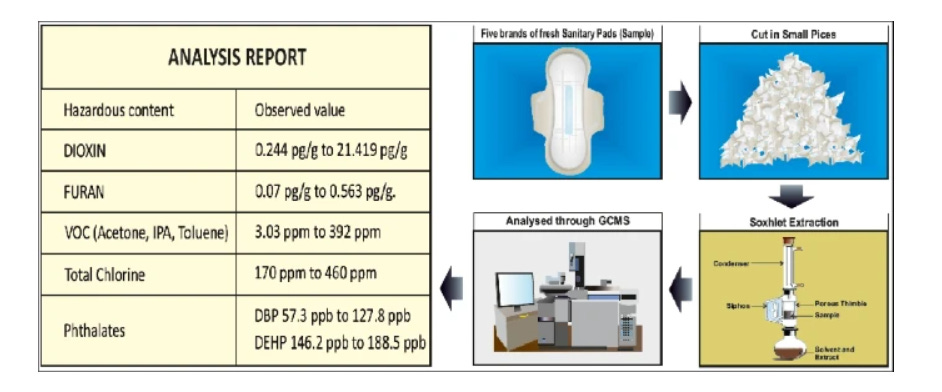

It is no secret now that the common sanitary pads used by women contain harmful toxins that affect a woman’s bleeding, pregnancy and overall health. Several research organisations have performed varied analyses on sanitary pads used all over India.

Toxics Link, a Delhi based NGO published a detailed report from their analysis which is freely available to the public. I’ll consider some of their primary findings in this essay but if you wish to read it for yourself, you can find their report in entirety here. Another study that echos similar findings can be found here.

The structure of the vagina is such that its skin is much more permeable than our skin in other parts of the body which means that it paves way for the transfer of chemicals directly into the bloodstream. If any chemicals are absorbed, their destination is often some female reproductive organ.

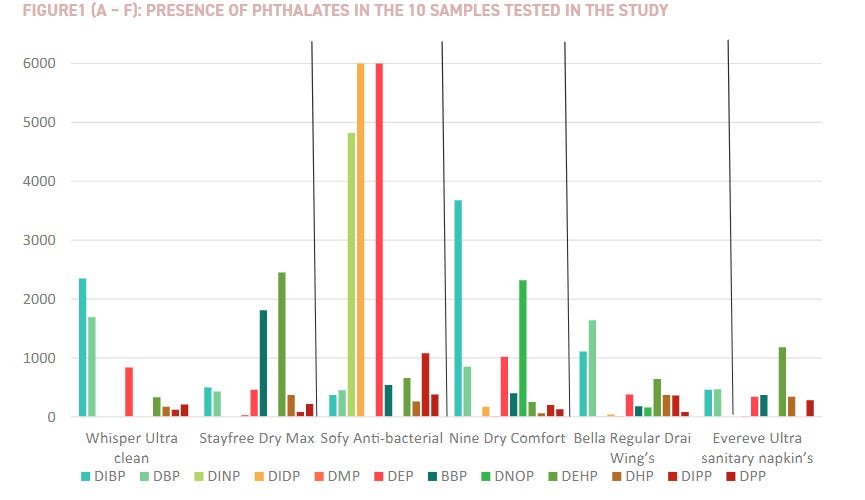

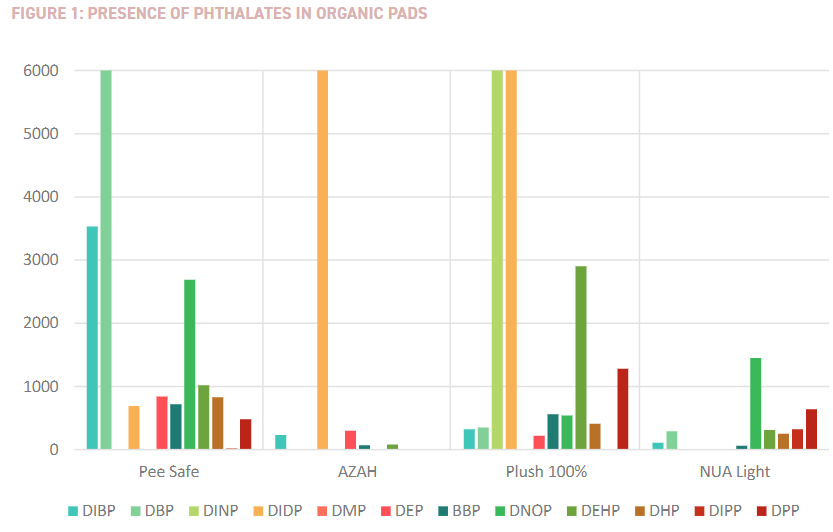

Phthalates are a harmful chemical component that are used extensively in pads as an adhesive to stick together the various layers of a pad. They are also used to increase softness and flexibility. These phthalates are found in other plastic-based products as well.

Let us look at some effects of phthalates on the human body:

increased chances of early menarche (arrival of the first period)

rapid breast development

amplification of breast cancer

found in high concentrations in the plasma of women with endometriosis

preterm births in pregnant women

risk of pregnancy-induced hypertensive diseases

linked to cause of early asthma

cardiovascular risks

insulin resistance

Another widely used component that has been proven to be harmful to the female body is Volatile Organic Compounds which are used in pads for fragrance, absorbance and as adhesives.

Let us look at some effects of phthalates on the human body:

harmful neurologic effects on the brain such as paralysis and memory loss

menstrual cycle issues

loss of appetite

tiredness

So, what is the solution? Perhaps we should all move to organic pads? The report suggests otherwise.

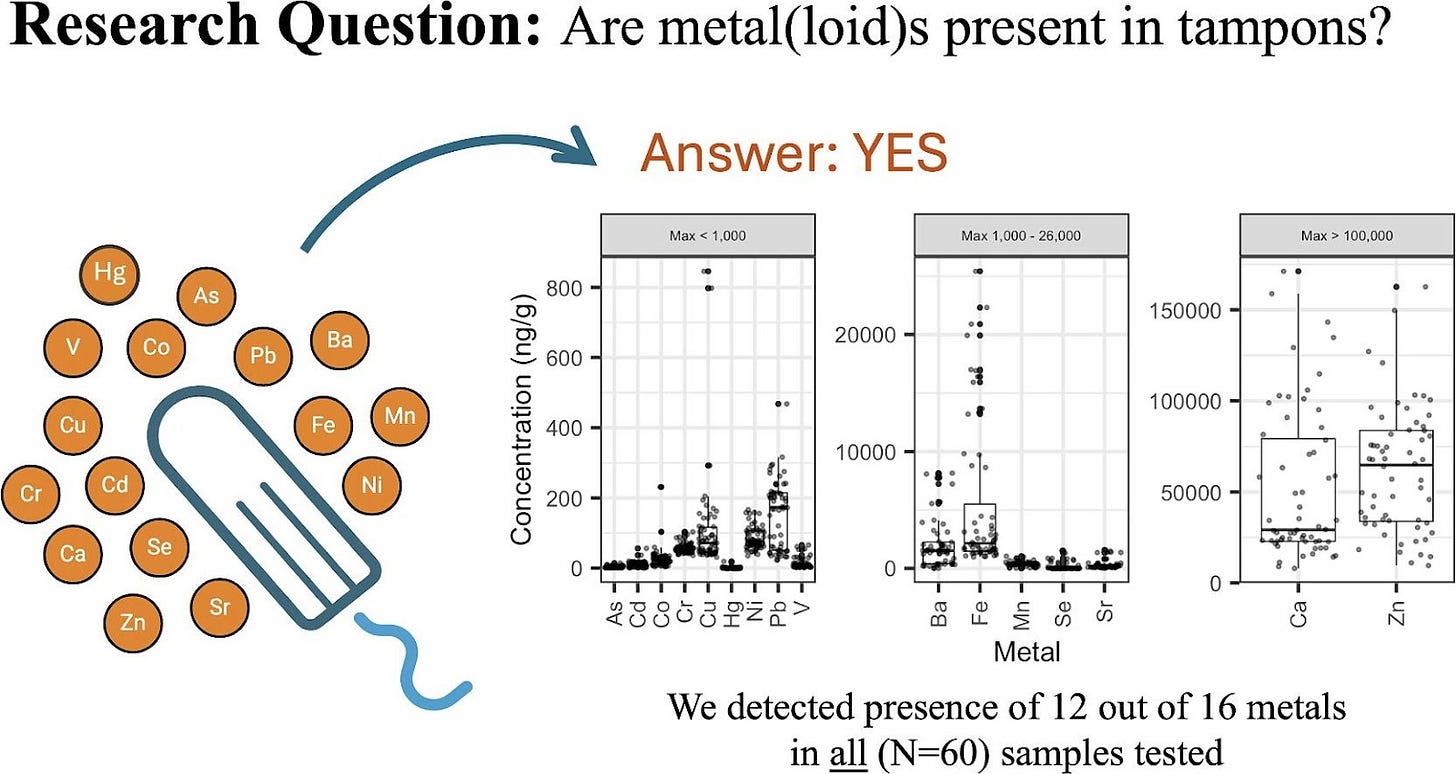

Maybe we should all ban sanitary napkins and consider tampons. A recent study found that several harmful metals and metalloids are present in tampons.

You can read the complete research paper here.

Some of these metals detected have no ‘safe exposure’ index meaning that they are absolutely and completely harmful to the women that use these tampons. These include but are not limited to lead, arsenic, cadmium, zinc, cobalt, chromium copper and mercury.

When we have conversations about menstrual sanitation, it is pertinent to remember that majority of the women in a country like India can’t even afford sanitary napkins and often resort to outdated methods of period flow management which does not support modern lifestyle and requirements. This hampers a girl child’s growth preventing her from going to school, pursuing higher education and affects her on a deep mental and emotional level.

We need to think about how we are going to create affordable sanitation for menstruating women of all economic backgrounds, especially considering the fact that the current solutions are harmful, toxic and hazardous both to the women using them and to the environment.

Chapter 4: A Glimpse into The Female Healthcare Crisis

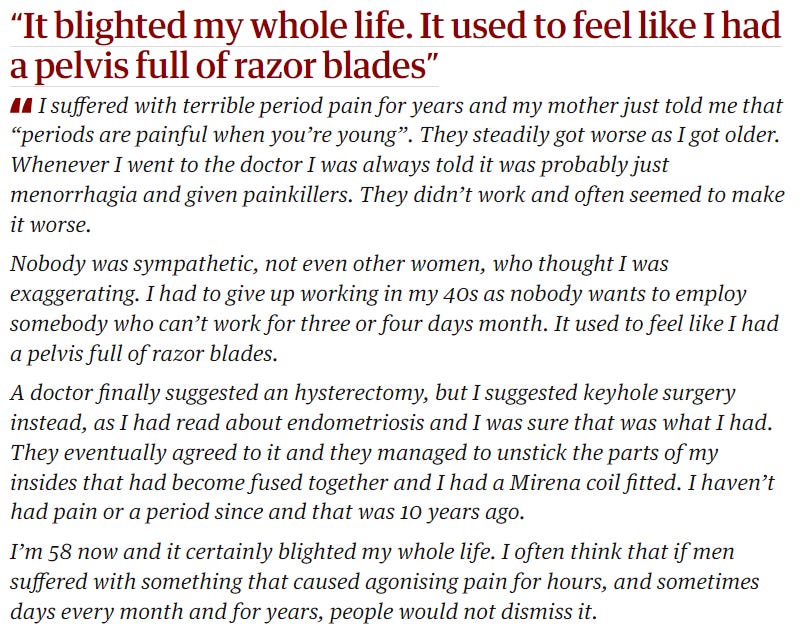

I want you to imagine a metal wire which is sturdy and has thorns embedded into it, kind of like barbed wire. Imagine someone wraps this around your lower abdomen and hammers it in. Sounds painful right? What I’d just described was how most women describe period pain, commonly referred to as period cramps.

I’d like for you to take a second and read the stories of the women in this article from The Guardian. Though 9 years old, not much has changed.

While most doctors dismiss such heavy pain as ‘normal’ for a woman to have, many women have stepped up saying that their endometriosis could have been diagnosed earlier if doctors had just taken their pain seriously. It’s jarring to see the number of women who’ve had to tolerate endometriosis, suffer through miscarriages and other reproductive disorders simply because doctors wouldn’t take their pain seriously.

From incompetent methods of pain management to epidurals falling off during labour to a broken needle left in the woman’s spine for years, women and their bodies have been continually dismissed and played around with. It breaks my heart to write this and I hope I’ll find the courage to expand on this in the upcoming weeks because I believe it needs dedicated focus.

Chapter 5: Final Thoughts

As Maria Schwartz said: Menstruation is the only blood that is not born from violence, yet it's the one that disgusts [you] the most. Throughout history, menstruating women have been ostracised in various cultures. Menstrual oppression in India is not just about one problem, but a web of challenges that women face every day, from harmful sanitary products to the enduring stigma around menstruation.

If we are to see a meaningful change, it must begin with a commitment to reform on multiple fronts. We need affordable access to healthy and safe menstrual products, prioritising effectiveness along with chemical-free solutions. Any innovations that arise mustn’t deepen the economic divide between women.

Along with this, we must focus on sex education, where women are taught about their bodies and the biology of menstruation without shame or discomfort. It is disheartening to see school teachers shy away from the topic, treating it as something embarrassing rather than natural. In extension, boys must also be included in basic educational conversations. It should not be treated as some secret or mystery that they are excluded from, because we must dismantle the stigma and foster empathy from an early age.

Equally important is the need for pain management and early detection of reproductive health issues. Simply taking women's pain seriously could lead to better diagnosis of conditions like endometriosis, PCOS, and other disorders whose symptomps are often dismissed as normal. Healthcare systems must be reformed to support women in managing their menstrual health with the same urgency as any other medical condition.

And none of this would matter if we don’t address the underlying societal attitudes that perpetuate menstrual oppression. Untouchability practices, exclusion, and silence around menstruation must be eradicated from our homes and communities. True change begins with each of us, as we challenge these harmful practices and create an environment where menstruation is seen as a dignified part of life.

A year back, I was combing my hair in attempts to braid it when my grandmother offered to help me. This was six years after the incident I began this essay with—the vitriol from my grandmother upon my brother touching me. I refused and she insisted—both of us engaged in this back and forth for a few moments before I said: Paati, I am on my period. I expected her gaze to drop from my face, a turned head and silence.

Instead, she shrugged her shoulders and said something akin to: so what? She went on to pick the comb, untangle the knots in my hair with her patient fingers and braid my curly hair. I am twenty and I don’t know much about the world but I think this is what generational healing looks like. If not for me, at least for her daughter, at least for herself.

Further Reading

If Men Could Menstruate by Gloria Steinem

Ground Report: Menstruating women are still banished from their homes in rural TN

How menstrual segregation thrives in urban households

From heart disease to IUDs: How doctors dismiss women’s pain